Becoming hungry before eating a meal is a normal experience, it’s something we as humans are meant to experience every day, multiple times per day. As children, we are much better at eating when we feel hungry, stopping when we feel full, and adjusting our daily intake in a way that we eat less at a meal if we’ve eaten more earlier in the day (Birch et al, 1991).

Over time, as more and more external factors impact when we choose to eat, most people have lost that reciprocal relationship (Russell & Russell, 2021; Herman & Policy, 2008 ). One of the many reasons that we eat when we aren’t hungry is that many of us have built up a fear of experiencing the feeling of hunger and oftentimes we plan our day of eating around avoiding that feeling. Eating in the absence of hunger sets you up to eat more calories than your body really needs which can lead to challenges maintaining your weight and result in weight gain over time. Hunger is not a bad thing, it’s not an emergency and as long as there are no underlying medical conditions, it is a perfectly healthy experience.

When you are trying to lose weight, you will likely have to work on getting to a point where you accept and get comfortable with feeling hungry sometimes. No matter what approach you take (changes in diet, activity levels, or changes in both) to weight loss, it will only happen if you are consistently eating fewer calories than your body is expending (Hall K et al, 2012). If you are eating fewer calories than you need to maintain your weight, you will likely experience more regular feelings of hunger.

While hunger is normal and is expected to happen daily (even more so when you are trying to lose weight) it can also create a barrier to weight loss if it becomes excessive or difficult to manage. It can make it more challenging to stick with your reduced-calorie plan long enough for weight loss to occur because when we are hungry, it’s really hard to say no to food! There are certain food choices you can make to impact hunger and help set you up for an easier, more enjoyable, “less hungry” path to weight loss. Let’s first take a look at the cyclic nature of human appetite to set up the ideas behind what we are going to focus on today.

The Cycle of Hunger

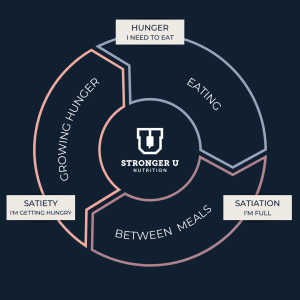

Appetite (our desire to eat food) is both a physiological and psychological experience that happens in a cyclic fashion for humans (Blundell et al, 2010). We are triggered to want to consume food by some factor (hunger caused by physiological changes in our body that tell our brain it’s time to eat or psychological associations or habits such as seeing or smelling food, time of day, other environmental or social factors that lead to desired to eat food even in the absence of physiologically based hunger), we start eating, we eat until a stopping point (satiation), and then there is some time in between eating (satiety) until another trigger causes the desire to eat and the cycle repeats.

While there are many, many, MANY factors that impact appetite and hunger, we are going to focus on the role of one specific component of this cycle – satiety. Satiety is the time span between when you last ate and when you have an appetite to eat again. If your goal is to either lose or maintain your current weight, there are benefits to making food selections that will allow you to feel satisfied (and not hungry!) in between meals and snacks for an extended period of time.

The Science Behind Satiety

Satiety is influenced by many factors including cognitive, sensory, and nutrient cues. While our main focus will be specifically on the role that nutrients and the types of foods you eat on satiety, I do want to briefly mention the role of these other cues as well first.

Our brain is a very powerful thing. If we believe that a particular food is more satiating than another, then is it true in our reality. For example, in one research study, participants consumed two fruit smoothies on two separate occasions and were asked to rate how full they were for a few hours after they drank them (Brunstrom et al. 2011). Participants were told that one of the smoothies had a much larger amount of fruit in it than the other. Participants consistently rated that they felt more full for a longer period of time after drinking the smoothie that they believed had more fruit. What the participants did not know is that the smoothies were actually the exact same!

There are many other instances in research that show the power of our thoughts related to satiety such as the believed impact of the texture/form of food consumed on how full it makes us (Cassady et al. 2012) as well as our memory of what we most recently ate. If we eat while distracted, that can cause us to eat more at that specific eating occasion but it can also reduce our ability to accurately recall how much we ate which can lead to eating more than we want at the next meal too (Higgs and Spetter 2018)! A thought such as “I hardly ate anything for breakfast, I’ll have this extra slice of pizza for lunch”, if accurate may be appropriate for assisting with managing daily energy balance BUT if the recalled breakfast was actually much higher in calories then remembered, that extra slice of pizza can put us over what we need.

Depending on your goals, it may be helpful to work on your thoughts about how filling your foods are as thoughts alone can have an impact on your food choices and successful movement towards your weight goals.

Energy Density of Foods

Beyond changing thoughts surrounding food, we can also make food selections that help us stay full as long as possible between meals and snacks. One characteristic of food that tends to have a big impact on the satiating effects of a meal/snack is the energy density of the foods consumed.

Energy density refers to the amount or volume of food you eat compared to the number of calories it provides. More specifically, the energy density of a food is calculated by dividing the number of calories in the food by the weight of the food. High energy density foods have a large number of calories per weight of food and low energy density foods have fewer calories per weight.

Higher energy density foods include foods that are higher in fat and added sugars such as fried foods, baked goods, nuts, seeds, and grains. Low energy density foods are lower in fat (nonfat dairy foods are lower in energy density than high-fat dairy foods), and include higher water (fruits and vegetables- water adds 0 calories to a food) and air (popcorn – air adds 0 calories to a food) content as well as more fiber (fiber adds bulk to foods and we can only generate a few calories from it). Low energy-density foods include fruits, most vegetables, soups, and popcorn.

Lower energy density foods tend to be more satiating for a lower amount of calories. When someone is trying to lose weight, selecting more foods that are lower in energy density can really help you feel more full between meals even while eating fewer calories (Rolls et al., 2005).

There are a lot of reasons for this. For one, humans tend to like to eat the same overall volume of food each day. So, if you want to eat fewer calories while still eating the same amount of volume, eating more lower energy density foods will allow you to do that.

Second, there is a visual component to this too. When we see a large plate full of food, we tend to think it will be more filling compared to a plate with less food on it. See the example picture below. Look at how much more the lower energy density fruit option fills up the plate compared to the higher energy-dense cookies.

Here’s a picture of a comparison on the same amount of calories (~100 calories) of a high energy density food (3 Oreo thin cookies – 22 grams) and a plate of berries (100 grams of strawberries, 75 grams of blueberries, and 50 grams of blackberries).

We eat not only with our mouth but also with our eyes and our eyes can clearly see that you get way more food by choosing the plate with the berries. And remember from above, when we think we ate a lot of food, we tell our brains that we ate plenty and don’t need to overindulge at the next meal. This can be really helpful when the overall goal is to stick to eating an amount of energy needed to lose weight! Thirdly, since many lower energy density foods also have a high amount of fiber (fruits and veggies, in particular), we also feel more full between meals from the higher fiber content which we’ll talk about more in just a bit.

The Macro Factors

Protein

Another important factor determining the impact of food selection on satiety is the macronutrient (carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) content of that meal. Research has accumulated over time that shows a hierarchy of satiety such that under circumstances of the same number of calories eaten, protein is the most satiating, followed by carbohydrates and finally fats (Halton & Hu, 2004). In one study that examined this comparison, participants were given a shake to consume prior to getting access to buffet lunch 90 minutes later on 4 different occasions (Poppitt, et al., 1998). Results showed that after consuming the shake that was highest in protein, participants reported feeling more full and ate less food at the following buffet lunch.

Research on longer-term studies has also shown that higher protein intake leads to a sustained, greater rating of satiety as well as has an impact on leading to reduced energy intake and weight loss (Weigle et al., 2005). These changes occurred in participants without them even being told to follow a lower calorie program!

In addition to protein being the most satiating macronutrient, consuming a higher protein diet is also associated with a higher required thermic effect a food (this is the number of calories it takes to digest and absorb a food so you burn more calories to process and use protein than the other macros) as well as the maintenance of more muscle mass when losing weight (Halton & Hu, 2004; Magkos, 2020). So overall it’s an important macronutrient to focus on for a variety of benefits, particularly when you are in the process of losing weight.

Fiber

We touched on fiber a bit when discussing the energy density of a food since fiber is a component of food that adds bulk without adding many calories but it may have an impact on satiety in other ways as well. Research has found that soluble fiber and particularly soluble fiber called 𝛃-glucan that is found in oats can have a marked influence on satiety (Rebello, et al., 2016). The way in which this fiber impacts satiety is that it changes the viscosity of food in the gut which causes digestion and absorption to slow down which in turn has an impact on the satiety signals that are sent to the brain. A fairly recent review study confirmed that specific types of fibers may have an impact on satiety and energy intake while others may not (Clark & Slavin, 2013).

Alcohol

It is also important to mention the impact that alcohol (a component in many people’s diet that provides calories but it’s not actually considered to be a nutrient, it is a drug) has on satiety. Research shows that calories added in the form of alcohol have no impact on making you feel more full at all. In fact, the consumption of alcohol has an impact of increasing your appetite and making you want to eat more (Tremblay, et al. 1995). So not only are you not feeling full even after consuming calories from alcohol (and those calories still count when considering weight management) but you may also feel a desire to eat more food after consuming alcohol. Overall, if managing hunger is the main priority for you, reducing or eliminating alcohol consumption would be beneficial.

In summary, appetite and hunger are impacted by a wide variety of factors. One factor that we can control related to managing hunger in between meals is our food choices. If we want to reduce feelings of hunger to support consuming an appropriate amount of calories to maintain or lose weight, selecting foods that are the most satiating can help with that. Foods that keep up full the longest include foods that are low in energy density (fruits, veggies, other foods with high water, fiber, or air content) and high in protein (meats, dairy, soy) and fiber (fruits, veggies, and oats). Making most of your food selections from these categories will provide you with a strong base diet that can help lead you towards your weight loss and weight maintenance goals!

References

Birch L, Johnson S, Andresen G, Peres J, Schulte M. (1991) The Variability of Young Children’s Energy Intake. N Engl J Med; 324: 232–5.

Blundell J, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, Jebb S., Livingstone B, Lluch A, Mela D, Salah S, Schuring E, van der Knaap H & Westerterp M. (2010). Appetite control: methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obesity Reviews;11(3): 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00714.x

Brunstrom J, Brown S, Hinton E, Rogers P & Fay S. (2011). ‘Expected satiety’ changes hunger and fullness in the inter-meal interval. Appetite; 56(2): 310–315. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.002.

Cassady B, Considine R, & Mattes R. (2012). Beverage consumption, appetite, and energy intake: What did you expect? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; 95(3): 587–593. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.025437.

Clark M & Slavin J. (2013) The Effect of Fiber on Satiety and Food Intake: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition; 32(3): 200-211, DOI: 10.1080/07315724.2013.791194

Halton & Hu. (2004) The Effects of High Protein Diets on Thermogenesis, Satiety and Weight Loss: A Critical Review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition; 23(5): 373-385, DOI: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719381

Hall K, Heymsfield S, Kemnitz J, Klein S, Schoeller D, Speakman J. (2012). Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; 95(4):989–994, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.036350

Herman C & Polivy J. (2008). External cues in the control of food intake in humans: The sensory-normative distinction. Physiology & Behavior; 94(5):722-728.

Higgs S & Spetter M. (2018). Cognitive control of eating: The role of memory in appetite and weight gain. Current Obesity Reports; 7(1):50–59.

Magkos F. (2020). The role of dietary protein in obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord; 21:329–340 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-020-09576-3

Poppitt S, McCormack D & Buffenstein R. (1998). Short-term effects of macronutrient preloads on appetite and energy intake in lean women. Physiology & Behavior; 64(3):279–285.

Rebello C, O’Neil C & Greenway F. (2016), Dietary fiber and satiety: the effects of oats on satiety. Nutrition Reviews; 74(2): 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv063

Rolls B, Drewnowski A & Ledikwe J. (2005). Changing the Energy Density of the Diet as a Strategy for Weight Management. Journal of the American Dietetic Association; 105(5); 98-103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002822305002956

Russell A & Russell C. (2021). Appetite self-regulation declines across childhood while general self-regulation improves: A narrative review of the origins and development of appetite self-regulation. Appetite; 162.

Schroeder N, Gallaher D, Arndt EA et al. (2009). Influence of whole grain barley, whole grain wheat, and refined rice-based foods on short-term satiety and energy intake. Appetite; 53: 363–369.

Tremblay, A., Wouters, E., Wenker, M., St-Pierre, S., Bouchard, C., and Després, J.P. (1995). Alcohol and a high-fat diet: a combination favoring overfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr ; 62: 639–644. PMID:7661127

Weigle D, Breen P, Matthys C, et al. (2005), A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; 82: 41–8.